Operation Cobra

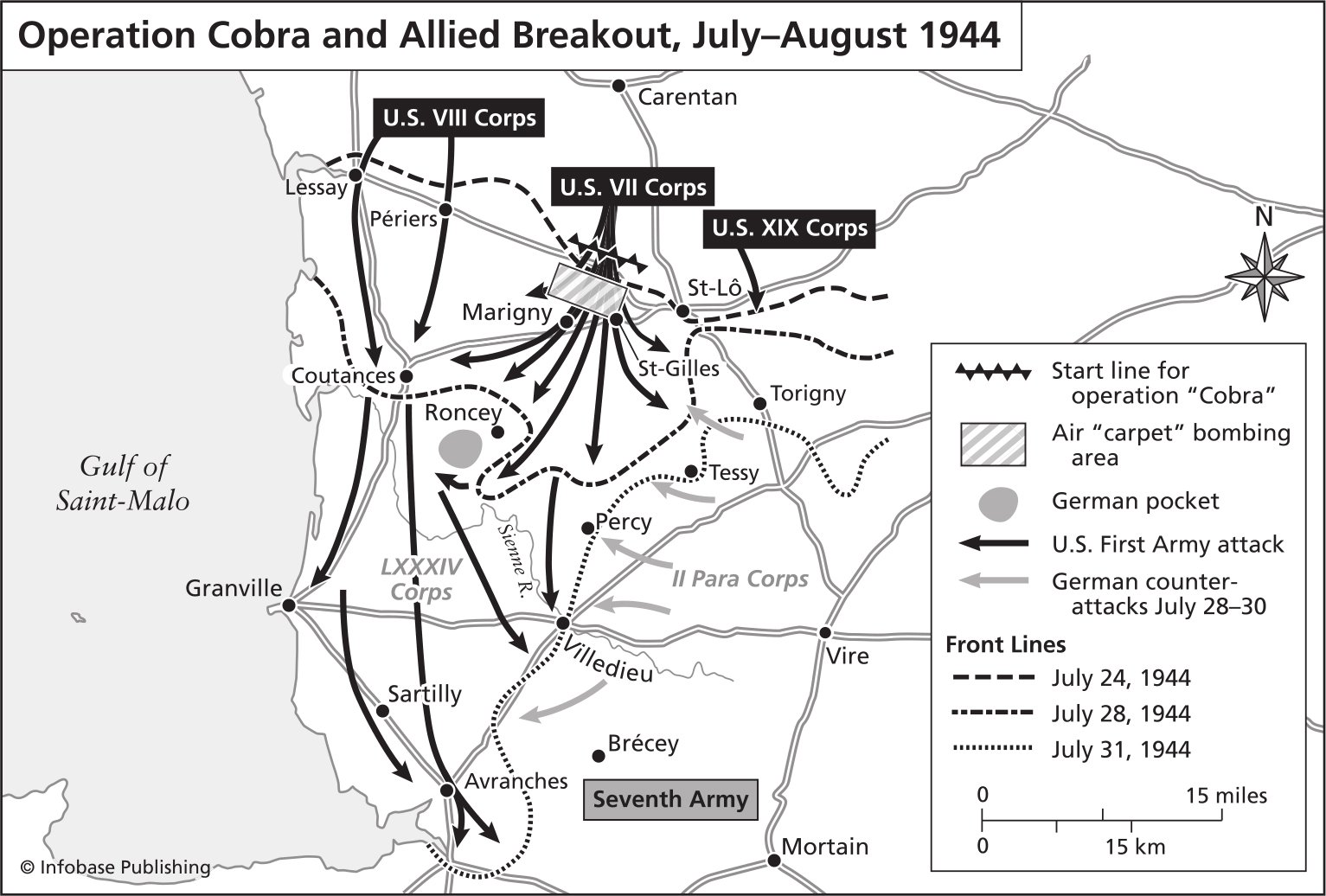

On July 21, the Germans intercepted a radio message calling American commanders to a staff meeting. This confirmed their suspicion that the American First Army was preparing a major offensive, but they still did not know where. General Hausser, after the heavy fighting around Saint-Lô, counted on a raid south-east through the Vire valley from Saint-Lô to Torigni. However, General Field Marshal von Kluge was convinced that the main attack in Normandy would come from the British on the Caen front. The Allies had a huge advantage in the shadow world of intercepted messages. General Bradley knew from some sources that the overstretched German forces were about to collapse. The moment for a breakthrough was at hand. The execution of this breakthrough was named ‘Operation Cobra.

The bombing of Operation Cobra

Bradley needed good visibility. He desperately wanted to break open the front with heavy bombers, but he also wanted to avoid making the same big mistake as at Goodwood, when the advance had not been fast enough to fully exploit the shock effect. Before launching his major offensive, Bradley had to fly back to Britain to discuss the plans for the large-scale bombing campaign with the Air Force. The idea, as with most major attacks, was to attack the enemy first from the air and only then, when the enemy had been weakened by the bombing, would the infantry troops move in to eliminate the remaining resistance. The space between the bombardment site and the infantry position therefore had to be large enough so that one could not accidentally hit one’s own troops. But the greater the distance, the longer it took the infantry to conquer the terrain ahead and the more time the Germans had to reorganise for the coming attacks.

Eventually, the distance between the bombardments and the infantry was set at about 1200 metres. The meteorological reports indicated that the sky would be clear enough by noon on July 24, and 1 p.m. was chosen as the H-hour (the start of the attacks and Operation Cobra).

On July 24, despite the weather forecast, it seemed that the sky had not yet cleared. Leigh-Mallory , the commander of the air force during Operation Cobra, considered the visibility for his planes insufficient. He sent a message to London to postpone the attack by one day, but the bombers were already on their way. An order was given to the ground troops to abort the mission, but most of the troops ready to attack had not received the message. Most of the bombers, however, received the message in time and returned. Some dropped their bombs on the agreed target but the first plane in the forward line had a technical problem with the release mechanism and dropped its bombs north of the target. Aircraft in the same front line took this as a sign and dropped their bombs too. They fell directly on the front lines of the ground troops. There were 25 killed and 131 wounded.

The attack was postponed to July 25 and H-hour was set at 11:00. A little before that, again numerous bombers arrived, just as the day before, to clear the way. Visibility was good but there was a strong wind. The first bombs hit their target but the smoke from the explosions was carried away to the north by the wind. The rear bombers dropped their bombs above the smoke with the assumption that these were the targets as there was a huge mass of smoke. On the ground, as on the previous day, tank crews jumped back into their vehicles and closed the turrets, but the infantry and General McNair, who commanded some of the ground troops, were exposed. A total of 101 men in the forward infantry regiments were killed and 463 wounded. One of the doctors who came to help saw to his surprise that ‘the faces of the dead were still pink’. Presumably this was because they had not been killed by shrapnel, but by the blast waves. McNair was one of the dead. His body was taken to a field hospital whose staff promised secrecy. Operation Cobra had not yet been deployed and already 720 casualties had been inflicted by friendly fire. Against all odds, Bradley took the decision to launch Operation Cobra that very day.

Weakening of the Germans

The Germans were in much worse shape after the bombing. The day’s delay had confused the Germans and had not betrayed the American plan. Von Kluge thought that the bombing of July 24 might have been a diversionary tactic to mask a major British offensive. He immediately visited the front of Panzergroep West and discussed the situation with General Eberbach.

His suspicions seemed to be confirmed, for Montgomery launched Operation Spring at dawn the next morning, perfectly timed, just four hours before Operation Cobra actually began. In this operation, the 11th Canadian Corps tried to capture the heights at Verrières along the road from Caen, to Falaise. Although the offensive ended in dismal failure, the result could not have been better. Von Kluge became even more convinced that Falaise was the Allies’ main objective. It was therefore only after more than 24 hours after the start of Operation Cobra that he agreed to the transfer of two armoured divisions from the British to the American sector. It took another two days for them to reach full combat strength at the front. Montgomery had thus achieved his main objective with Goodwood and Spring, even if he did not succeed in forcing a breakthrough.

The heavy bombardment of July 25 had a devastating effect on the German soldiers and vehicles. The whole area looked like a moonscape; everything was burned and destroyed,’ wrote Bayerlein. It was impossible to bring in vehicles or repair damaged ones. The survivors behaved like lunatics and could not be deployed. In my opinion, hell is not as bad as what we experienced.’

Slow progress

The 4th Infantry Division managed to advance no further than about 2.5 kilometres. ‘The result of the first day hardly constituted a real breakthrough,’ the divisional headquarters acknowledged. The 9th Division to their right and the 30th Division to their left achieved little more. The bombing, it was generally felt, had had disappointingly little effect. But both commanders and troops were too cautious, which was partly the result of weeks of fighting in the bocage. Their corps commander, General Collins, then took a bold decision. He decided on July 26 to throw the armoured divisions into battle earlier than planned.

That morning, July 26, Collins had ordered the 1st Division together with a combat command of the 3rd Armoured Division to break through on the right. In the meantime, Brigadier Rose’s 2nd Armoured Division would attack from the left, initially with the 30th Division, and then advance alone due south towards Saint-Gilles.

Once Rose’s tank column was out of the bombed area and past Saint-Gilles, the pace of advance increased, even though it was now night, Rose saw no reason to stop in the dark. His armoured vehicles went around German positions. Some German vehicles joined them, believing the column to be one of their own retreating units, and were immediately captured.

On the road to Canisy in the south, Roses Shermans shot to pieces German semi-tracked vehicles equipped with only one machine gun. Canisy had been bombed by P-47 Thunderbolts and was on fire. The tank column took their time to search through the rubble. In the local chateau they found a German field hospital where they captured wounded soldiers, doctors and nurses. Rose did not want to waste time. He forced his men to drive on to Le Mesnil-Herman, more than 10 kilometres south of Saint-Lô.

Hickey’s combat command and the 1st Division moved south to Marigny, 6 kilometres beyond the Périers road, to Saint-Lô. But the town did not fall immediately. The roads were blocked with rubble and the walls of burning houses collapsed. The Americans captured nearly 200 Germans, many of whom were reinforcements who had just arrived from training battalions. By nightfall, Marigny was completely captured. American casualties were extremely low. One battalion reported only a dozen or so wounded throughout the day.

The breakthrough

The decisive breakthrough of the Americans had a striking effect on the morale of the Germans, Soldiers began to talk to each other in a way they had not done before. Klein, a senior non-commissioned officer in the Medical Corps, described the evening of July 26 when they were told to leave their dressing station south of Saint-Lô with 78 seriously wounded and to withdraw. He recorded the conversation of the wounded.

A corporal who had been awarded the German Cross in Gold for destroying five tanks on the Eastern Front said to him:

” Let me tell you something, Corpsman. This here in Normandy is no longer a war. The enemy is superior in both men and equipment. We are simply being sent to our deaths with inadequate weapons. Our commander (Hitler) does nothing to help us. No planes, insufficient ammunition for artillery, … Well, in my opinion the war is over. ”

At noon on July 27, Bradley issued new orders. Operation Cobra was going so well that he wanted a general advance towards Avranches, the gateway to Brittany. The commander of the British airborne troops, Lieutenant General Sir Frederick ‘Boy. Browning, had tried to convince Bradley of the idea of a parachute landing at Avranches in the German rear. But Bradley rejected the plan. An airborne landing would severely limit the flexibility he needed in Operation Cobra because it would morally commit them to the primary task of relieving the airborne forces.

It suddenly became clear to the German commanders what a huge disaster was in store for them. They had been slow to react, mainly due to the American tactic of cutting all cables and telephone lines. In several places, the German troops had no idea that there had been a breakthrough. Often, to their surprise, they discovered American troops far behind what they thought was the front line.

Although the sky was overcast on July 27, which saved the 2nd Panzer Division from air attack as they advanced towards the Vire, they did not cross the river at Tessy until that evening, sixty hours after the start of Operation Cobra. By then it was far too late to stop the American advance.

When the 6th Armoured Division reached Coutances on the west coast on July 27, they saw that their reconnaissance unit had already taken the town. They camped there that night and then continued on towards Granville. The German infantry were hiding in the hedges on both sides of the road, so the light tanks of the 6th Armoured Division were moving left and right with machine guns firing at 25 kilometres per hour along the road. Brigadier General Hickey’s column of the 3rd Armoured Division was also heading for Coutances. But General Collins, who joined them as well as Colonel Luckett of the 12th Infantry, criticised the 3rd Armoured Division for moving too cautiously.

For the American formations in the centre of the breakthrough, the advance on July 27 was more difficult. The armoured divisions were held up by the heavy military traffic on the roads; sometimes columns were up to 25 kilometres long. The obstacles were usually broken-down German vehicles blocking the road. Bradley had foreseen these problems and earmarked 15,000 engineers for Operation Cobra. Their main task was to make and keep accessible the major supply routes that ran through the breach. They had to fill craters in the roads, clean up destroyed German vehicles and even create diversions around cities in ruins.

The American advance along the coastal road accelerated. With the sea to their right, the 6th Armoured Division advanced almost 50 kilometres. Whenever they hit a roadblock, the Air Force liaison officer simply called in a squadron of P-47 Thunderbolts from his tank or semi-tracked vehicle, and the position was destroyed, usually within 15 minutes.

A fatal mistake

When Von Kluge heard that evening in La Roche-Guyon that the Seventh Army had decided to break out to the south-east, he lost his temper. Von Kluge called General Hausser and ordered him to immediately withdraw his order that he had made earlier. Hausser replied that it was probably already too late, but that he would try. At midnight an officer on a motor cycle finally reported to General Choltitz, but he could not get in touch with his divisions. They continued their attack in a south-easterly direction, away from the coast.

Von Kluge, who dared not dismiss Hausser for this mistake because he was of the Waffen-ss, ordered Pemsel to be replaced. General Choltitz, who was called back to take command of the Paris area, had to hand over the 84th Corps to General Elfeldt. Hitler was also furious when he heard that the road to Avranches, and thus to Brittany, was open. The OKW ordered an immediate counterattack. Von Kluge also urgently requested reinforcements. He asked for the 9th Panzer Division, which lay in the south of France, and more infantry divisions. This request was granted unusually quickly by the OKW.

Brigadier General Hickey’s 3rd Armoured Division Battle Command, following the German withdrawal, saw at Roncey that abandoned and broken German equipment was blocking the road to such an extent that it was impossible to move through the main street. The task force had to go through the backstreets to get out of the town. A tank dozer had to be used to clear the main road. So many German soldiers surrendered that there was nothing to do but to send them to the rear unguarded. When the 3rd Armoured Division arrived in the area around Grimesnil and Saint-Denis-le-Gast, an officer of the Medical Troops wrote in his diary ‘Terrible slaughter. Also enemy casualties crushed by our tanks’.

Brigadier General Rudolph-Christoph Baron von Gersdorff, the new Chief of Staff of the Seventh Army, who had arrived at the forward command post five kilometres north-east of Avranches on the afternoon of July 29, found a disastrous situation. No one had ordered the bridges to be blown up and there were no land links. Because the Germans had withdrawn from the coast, which Von Kluge had been so angry about, the American 6th and 4th Armoured Division hardly met any resistance. In the coastal town of Granville, the Germans started blowing up harbour installations at 1 a.m. and continued for five hours. The local commissariat de police reported that German soldiers were looting and stealing every vehicle they could find to escape to the south. An American tank platoon even drove past the Seventh Army command post 100 metres away without noticing it. General Hausser and his staff left at midnight and withdrew east of Mortain.

The Germans had practically no men left to defend the coast road. A reserve field battalion south of the La Sienne River had seized stragglers who had managed to slip through the American advance detachment. The 6th and 4th Armoured Divisions, already under Patton’s command, were well on their way to Avranches. Patton did not accept any excuse for delay. ‘We must outflank them before they regroup,’ he wrote in his diary on July 29, He was in high spirits. A breakthrough had been made. The breakthrough, which he believed was his by divine right, was about to begin.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error