The Falaise pocket

The formation of the Falaise pocket

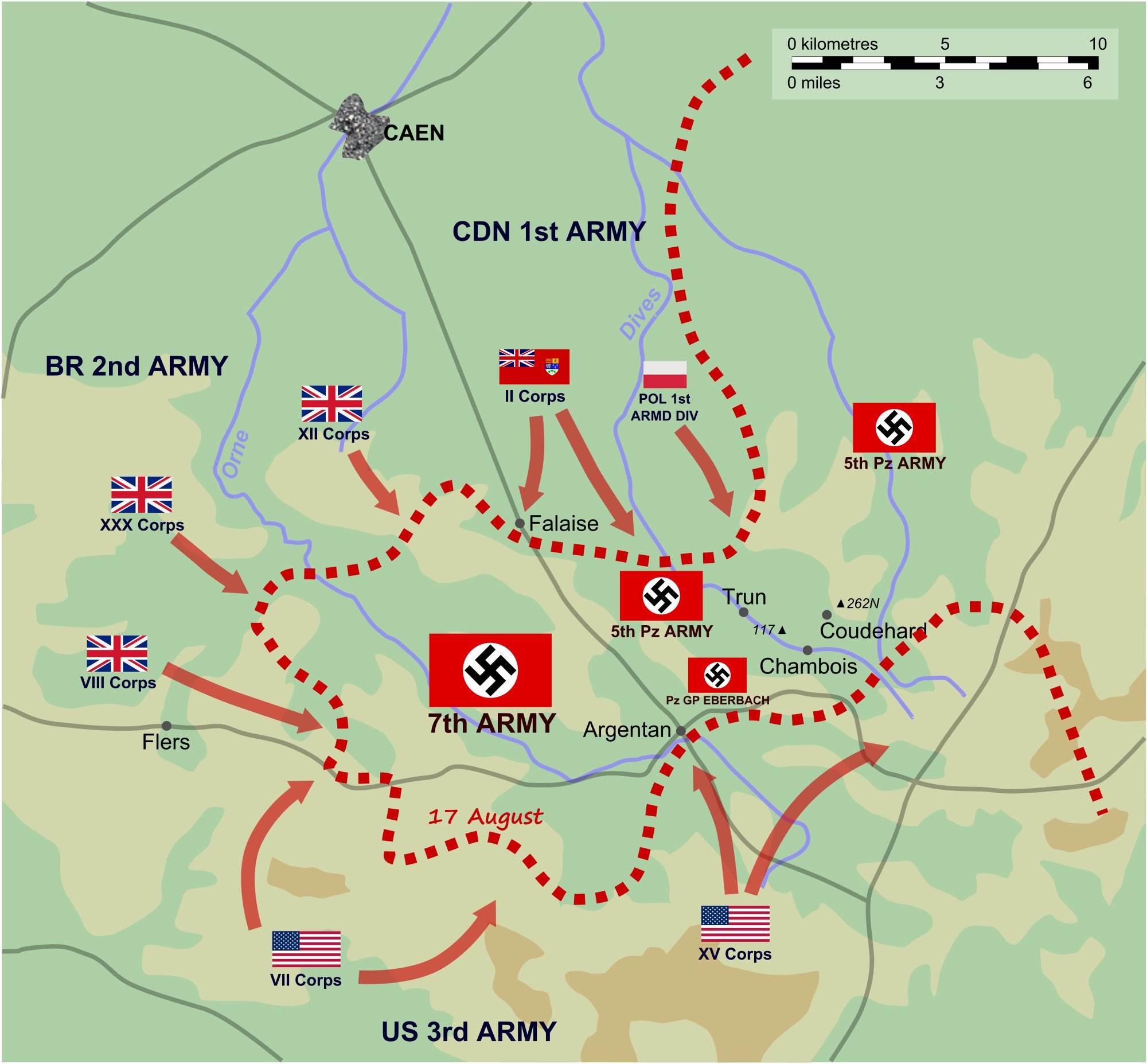

Due to the failure of the German counterattack on Mortain, during Operation Lüttich, Bradley and Montgomery decide to take the opportunity to encircle the retreating German troops in a large scale. If this encirclement would succeed, it would definitively cost the Germans the Battle of Normandy. This encirclement later became known as the Falaise pocket.

The American 15th Corps, which had liberated Le Mans on August 9, was the first to be ordered to advance quickly from the south, led by General Leclerc’s 2nd Armoured Division. On August 12, they captured Alençon and then advanced on Argentan.

Montgomery’s troops had to advance from the north after capturing Caen to close the Falaise pocket on their side. However, the Americans disapproved of Montgomery’s cautious and slow approach as it meant they had to wait longer than they had hoped.

The Falaise pocket is getting smaller

On August 16, the Falaise pocket was pulled tighter but it was far from being closed due to the delay of the Canadians and General Gerow’s 5th Corps at Argentan. On the same day, Hitler finally ordered his troops to retreat completely even though most of the Germans had already begun to do so a few days earlier.

Gersdorff, Chief of Staff of the Seventh Army, was able to drive through the breach between Trun and Chambois by car that day. One of the German generals noted that the hole looked disturbingly similar to the tattered diamond shape at Stalingrad, though of course it was much smaller.

The German 11th Armoured Corps was sent north-east of Argentan into the Forét de Gouffern to defend that corner of the gap, although it brought together less than forty tanks. The next day the remnants of two divisions were sent to Vimoutiers. General Hausser also sent the 2nd Ss-Panzerdivision Das Reich out of the hole. He wanted to have a force ready to counterattack from behind if the Allied troops tried to close the gap. Army officers, however, suspected that this was merely an attempt by the Waffen-ss to save its own skin.

While on the other side of the River Orne the remnants of the German Seventh Army retreated, the British 8th and 30th Corps advanced rapidly in the east and liberated place after place. We were greeted enthusiastically everywhere,’ wrote one British officer, ‘though many people still seem dazed and confused. The youngest don’t quite know what’s going on. I saw one little boy proudly make the Nazi salute as if it were the right thing to do, and others looked at their mothers to gauge whether it was all right if they waved.’

Falaise was taken on August 27. Now all that remained was to make contact with the American units which had already reached the outskirts of Argentan.

The ruthlessness of the pilots

The Allied pilots showed little mercy during the formation of the Falaise pocket. We let our rockets go,’ wrote an Australian Typhoon pilot, ‘and then we fired separately at the packed crowd of soldiers. We started firing, then slowly drew the cannon fire through the crowd and then we took off and made one round after another until we ran out of ammunition. After each round, which led to a large empty path with fallen soldiers, the space was almost immediately filled by other fleeing soldiers.’

General Luttwitz of the 2nd Panzerdivision looked upon the scene that day in horror. Mountains of vehicles, dead horses and dead soldiers were scattered over the road, and they increased in number by the hour. Gunner Eberhard Beck of the 277th Infantry Division saw a soldier sitting on a stone. He pulled him by the arm to pull him to safety, but the man rolled to the ground. He was already dead.

There were so many British and American squadrons firing at random at targets on the ground that there were countless instances of ‘own fire’. The ironic exclamation: ‘Take cover, boys, it could be ours!’ took on a new urgency. The headquarters of Bradley’s 12th Army Group acknowledged that ‘some British armoured vehicles had been attacked accidentally’, but pointed out that the British tank crews carried so much stuff on the outside that their distinctive white stars were often ‘covered in rubbish’.

Because of these random air raids, the Canadian 4th Armoured Division did not occupy Trun until the afternoon of August 18. The division was also hampered by the lethargy and incompetence of its commander, Major General George Kitching, and by Lieutenant General Guy Simonds’ plan that the armoured brigade should break away to lead the advance towards the Seine. On August 18, a detachment of the division reached Saint-Lambert-sur-Dives, halfway between Trun and Chambois, in the evening, but it was too weak to capture the village before reinforcements arrived.

By day, the Germans hid themselves and their vehicles from the Allied planes in the woods and orchards. At night, exhausted and starving German soldiers stumbled on, cursing their leaders who lost them in the dark. Many of them used French two-wheeled handcarts to carry their equipment or heavy weapons. They were suddenly joined by soldiers from services in the hinterland, such as detachments of shoemakers and tailors, all trying to escape but having no idea where they were going.

On August 20, to the despair of the Germans who had not yet managed to cross the Dives and the Trun to Chambois road, the day began as bright and serene as the previous days. As soon as the morning fog lifted, the American artillery opened fire and the fighter-bombers appeared at tree height with their breathtaking roar of aircraft engines.

Two of the tanks of the 2nd Panzer Division finally managed to knock out the American anti-tank vehicles that covered the road from Trun to Chambois, and they managed to cross over. This was the signal for a large-scale exploitation of the outbreak. A large number of reconnaissance cars, tanks, pieces of mechanised artillery etc. emerged from all kinds of hiding places.

In fact, early in the morning many more Germans had already come through the hole than the Allies thought at the time. And many more slipped through in the course of the day, especially in the Canadian sector which, despite persistent pleas for help from the men who were near Saint-Lambert, had not received proper reinforcements. The 4th Armoured Division was to prepare for the advance on the Seine but had not yet been relieved by the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division. Again, this major error in execution stemmed mainly from Montgomery’s indecision as to whether they would pursue a long encirclement towards the Seine or a closure of the breach at the Dives.

Meindl believed that the only way to get himself and his troops through the breach was to launch an attack on the flanks towards the north. The improvised attack was launched and, as if by a miracle, they captured the Coudehard ridge at 4.30 p.m. when Waffen-ss tanks attacked from the other side. They broke through the encirclement and created a breach almost 3 kilometres wide. The few prisoners of war they captured confirmed that they had taken on the 1st Polish Panzer Division.

General Hausser, meanwhile, had been seriously injured. He was evacuated on the back of one of the few tanks left. Meindl’s main concern that afternoon was the evacuation of the remaining wounded in a column of clearly marked ambulances. ‘Not a shot was fired at them,’ wrote Meindl, ‘and I deeply gratified the chivalrous enemy.’

He waited half an hour after the column had disappeared before sending out fighting troops, ‘so that no suspicion could arise among the enemy that we had taken any advantage of the situation’.

The Falaise pocket is closed

On August 24, the Polish Panzer Division, which had been cut off around Mont Ormel, finally received reinforcements and new supplies from the Canadian troops. The gap had been closed. General Eberbach, realising that hardly any men would escape now, ordered the remnants of the 11th Ss-Panzerkorps to retreat to the Seine. The badly wounded General Hausser was taken to the Seventh Army’s temporary command post at Le Sap, where he asked General Funck to take over command. (General Eberbach took over two days later.) Staff officers began to assemble and reorganise the troops. They discovered to their surprise that in many cases more than 2,000 men per division had escaped, but this still seemed on the high side.

The German troops that remained offered little resistance. It was a day for collecting prisoners of war. ‘The yanks say they made hundreds all day,’ wrote Major Julius Neave in his diary. `The 6th Durham Light Infantry just reported that they are in a splendid position and can see hundreds coming towards them.’ For many units chasing Germans out of the woods was a game. But there were tragedies too. The Germans had left hundreds of mines and booby traps in Ecouché. A boy of about ten years old came out of the church towards us,’ a young American officer from the 38th Reconnaissance Squadron told me, ‘and was blown up by one of those anti-personnel mines. British engineers who had just arrived started clearing mines to prevent more accidents. They cleared 240 of them.

In addition to the large numbers of prisoners of war, there were thousands of German wounded to be cared for. During the clearing operations, a German field hospital with 250 wounded was discovered deep in the Forét de Gouffern. However, most of the wounded left behind in the encirclement had received no medical attention at all.

Montgomery issued a statement to the 21st Army Group on August 24. ‘The victory that has just been won is complete and decisive “The Lord, great in battle, has given us the victory’: But some did not feel that this victory was ‘complete and decisive’. According to General Eberbach’s estimates, perhaps 20,000 men, 25 tanks; and 50 pieces of mechanised artillery had escaped the encirclement of the Falaise pocket. The loss of tanks through lack of fuel was greater than that of all enemy weapons combined,’ he wrote afterwards. According to Gersdorff, 20,000 to 30,000 men had managed to cross the Seine and escape the Falaise pocket.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error