Sword beach

The battle for the bridgehead on the River Orne had been going on for six hours when Hobart’s armoured forces led the British and Canadian assault troops to the rocky beaches at Ouistreham and Lion-sur-Mer, to Langrune and Courseulles, to La Rivière and Le Hamel. These beaches were codenamed ‘Sword Beach’.

Far out on the right flank, behind the protruding rocks of Port-en-Bessin, the Americans had suffered heavy losses on Omaha Beach for an hour as German guns took fire from the long bare beach. Hopes of launching a surprise attack on the eastern side were dashed but it seemed to make little difference as the enemy was under sustained attack not only from the sea but also from the air.

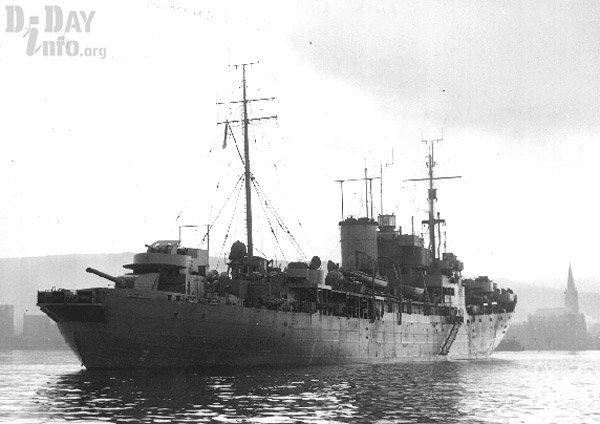

A heavy smoke screen obscured the whole of the British left flank from the heavy coastal batteries of Le Havre, which had been bombed a hundred times from the air, without success. They posed a greater danger than the rough sea to the convoys assembled more than thirteen kilometres from the coast and launching their landing craft. Enemy E-boats, raiding from Le Havre, emerged briefly from the smoke and launched four torpedoes, one of which sank a Norwegian destroyer and another forced the Largs, the command ship, to turn back quickly to avoid the dangerous projectile. The other two torpedoes passed between the warships without doing any damage.

Heavy air bombardments, which started shortly after dawn, were followed by shelling from the sea, firing an enormous amount of shells of all calibres at the narrow coastal strips. The outlines of the buildings rose up like shapeless fragments of stone from the mist of smoke and flame. The helmsman of one of the storm boats hung over the stern to act as a living helm. Men drowned, but the storm boats and the landing craft bubbled along, borne up by the screaming, deafening violence of their own guns, which fired rocket launchers, Oerlikons and machine guns as they sailed towards Sword Beach. Mines, mortar shells and other shells lifted small boats and their contents out of the water before they broke to pieces in the explosions; explosions ripped the guts out of larger boats and turned them into flaming torches in which, miraculously, some men survived.

The strong wind swept the tide beyond the outer belt of barriers and there was nothing to do but to sail to the beach and try to navigate between the deadly barriers, the angle irons and the pointed stakes, only to end up on the beach in an avalanche of foam and water.

H-hour on Sword Beach

H-Hour was at 07.30 and the first armoured forces were due to reach Sword Beach at H-5. Force S (Sword) had put the DD tanks in the water three miles offshore and it was clear that it would only be thanks to the excellent seamanship of the crew, the 13/18th Hussars, if they arrived on time. The DDs were deep in the water with waves over a metre high constantly crashing over them. The monsters were almost invisible and a group of LCTs, crossing their course, sunk two and would have sunk more, had not a salvo of rockets fallen short, forcing the LCTs to change course.

When the shelling by the warships ended, the sea in front of the beach was full of small craft and wreckage and, almost exactly in time, the flail tanks at the head of eight assault groups drove onto Sword Beach. Driving towards the beach roads, they began to defuse mines, meanwhile taking fire from the enemy positions. They were followed by the whole ‘collection’ of armoured monsters (AVREs – Assault Vehicle, Royal Engineers), the Bobbins, the tanks that could lay bridges, and the foot search tanks (Petards). Of the 40 DD tanks, 33 rolled out of the water just in time to help the infantry across the most dangerous part of the beach.

Within minutes, the wreckage of the destroyed tanks added a grotesque dimension to the inferno. A flail tank without tracks kept firing at an 88-mm gun, another exploded, one of the AVREs lost its bridge and somewhere a DD tank got tangled in a tangle of steel and barbed wire. Engineers, crawling out of the tanks, pushed on and cleared the obstructions by hand. In the water in front of the beach soldiers jumped out of burning landing craft and made their way to the beach through the remains of men and their equipment. On the right flank, the 1st Battalion of the South Lancashire Regiment, which spearheaded the 8th Infantry Brigade, moved quickly behind the tanks across the beach and began to attack enemy bunkers. The 2nd Battalion, the East Yorkshire Regiment, their brothers in arms on the left flank, had more difficulty in gaining a foothold. All along the beach, from left to right, the enemy small arms and mortar fire was intense. On the Périers heights, German armoured artillery was positioned; the enemy divisional artillery was firing at the barrage balloons.

Order is emerging from the chaos

Gradually order began to be brought to the chaos, despite the fact that more and more wrecks were being added to Sword Beach. By 09.30 hrs the Hobart ‘specials’, the armoured forces of the 22nd Dragoons, the Westminster Dragoons and the two squadrons of the 5th Assault Regiment, had cleared seven of the eight beach exits. The squadrons assembled at La Riva; some then went on to support the commandos in their fight for possession of the sluice gates at Ouistreham and in the capture of Lion-sur-Mer, while others acted as spearheads for the infantry advancing towards Caen.

The South Lancashires soon reached Hermanville, which lay more than two kilometres inland. There they faced the important Périers heights, on which Feuchtinger’s armoured guns were mounted and which were defended by the 716th Infantry Division. But the 8th Infantry Brigade was unable to continue the attack. Enemy artillery repulsed small armoured forces attacks and the infantry had to dig in at Hermanville.

By 11 a.m. the 185th Brigade was gathering its three battalions in the orchards near Hermanville. An immediate attack on the Périers heights was necessary, not only to break open the bridgehead on the road to Caen, but also to extend the bridgehead on the Orne. While the commando troops broke through quickly, the infantry, which was poorly led, followed at a much slower pace.

An additional reason for the slow progress of the front was the growing number of men and armoured forces, all trying to leave the beach, causing traffic jams in the narrow streets, side roads and beach exits. The tanks of the Staffordshire Yeomanry, whose job it was to bring the men of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry up the road to Caen, were stuck in the traffic. It was late when the guns on the Périers heights were finally silenced and the Shropshires could advance.

The front infantry did everything the leaders asked of them, but it was not enough. The East Yorkshires had taken a beating, five officers and 60 men dead and 140 wounded, but they had achieved their objectives. The Shropshires marched boldly out of Hermanville to meet the enemy, without any protection on their flanks. At 4 p.m. the battalion, reinforced by the mechanised guns and tanks of the Staffordshire Yeomanry, reached Biéville, barely six kilometres from Caen.

This soon proved to be a particularly difficult position, for Feuchtinger had finally received the orders he had requested, Rommel was in a flying hurry to get to his headquarters, Hitler had awakened and the German armoured forces were on their way. Near Biéville, 24 tanks of a strong German fighting group of the 21st Armoured Division, seeking an opening in the British attack formations, came into action against the Shropshires and their tanks. Mechanised guns put five enemy tanks out of action, after which the enemy withdrew. Despite the threat of the armoured forces, the Shropshires tried to advance further but were halted by intense fire from the densely wooded hills of Lébisey. The death toll was rising steadily; a new armoured attack could be launched at any moment and the flank battalions of the 185th Brigade were making extremely slow progress. To conquer Caen was an illusion.

But Feuchtinger’s armoured forces were no longer heading in that direction. The British, who had occupied the Périers heights, had pushed the battle group further west and the spearhead, which had had no success against either the Shropshires or the British guns, thundered northwards through the gap between the British and Canadian landing forces, 90 tanks strong.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error