Omaha beach

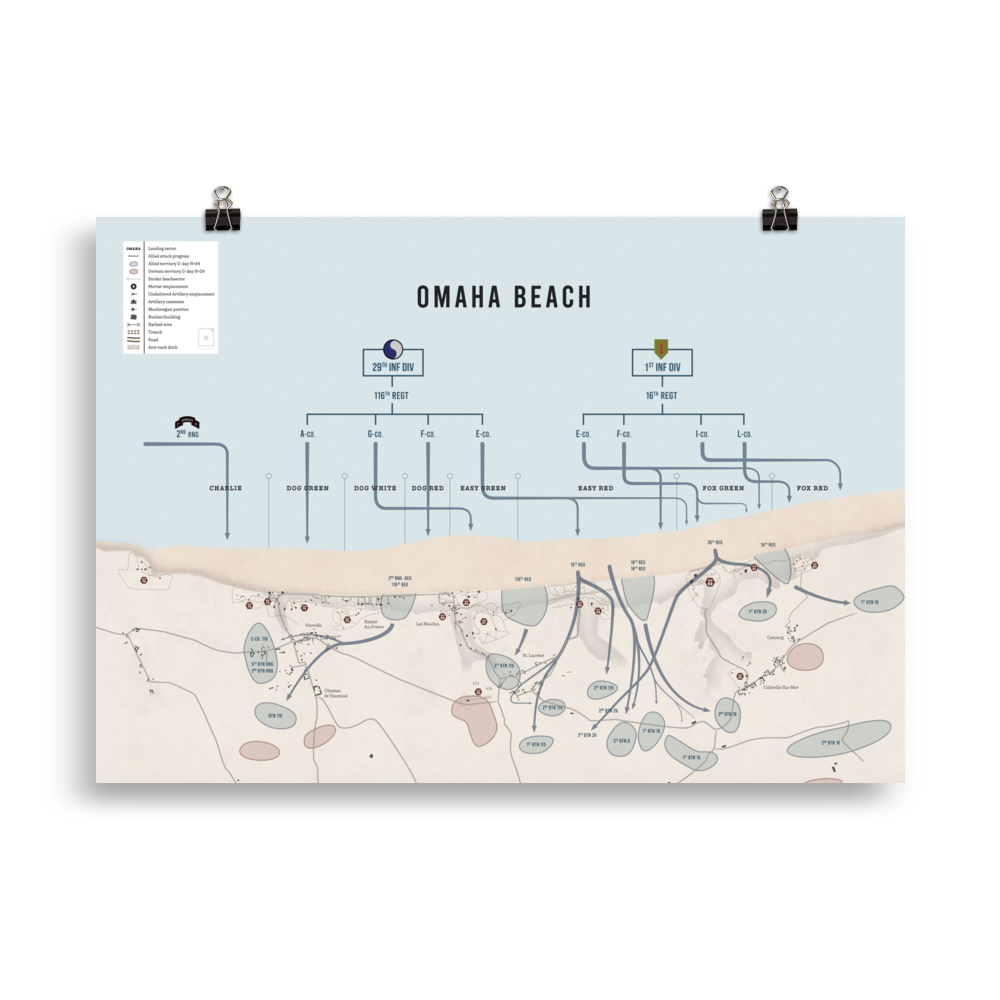

Omaha Beach lay between the jutting rocks of Pointe de la Percée to the west and Port-en-Bessin to the east, a narrow, gently curving beach, enclosed on the landward side by heights gradually rising 45 metres to a plateau with small fields enclosed by hedges, hollow roads and scattered hamlets of solid stone houses. It is sparsely populated; the largest village, Trevieres, which lies on the south side of the Aure some six kilometres inland, had no more than 800 inhabitants.

Three coastal villages, Vierville-sur-Mer, St. Laurent and Colleville-sur-Mer lie behind the border, each two to three kilometres apart. A narrow road, which runs 500 to 1000 metres behind the beach, connects the villages. Behind low seawalls of wood and brickwork, there is a stretch of paved promenade between Vierville and Saint-Laurent. From the villages, access roads lead here and there to the beaches, which end in narrow channels.

At low tide, the beach rises gradually towards the sea wall and in some places to a heavy gravel bank with stones of 5 centimetres in diameter, which forms an obstacle of about two and a half to three metres high between the beach and the heights covered with marram grass. The strong tidal current creates deep channels in the wet, ribbed sand.

The rocky outcrops of the heights along Omaha Beach had been used by the Germans to build concealed gun emplacements to bring down enfilading fire on the front part of the beach and the waterline and, behind the heavy gravel bank, the enemy had made trenches, connecting fortified points, bunkers and concrete gun emplacements, which were positioned to bring down a devastating crossfire on Omaha Beach. Light and heavy machine guns, 75- and 88-mm artillery could, at least in theory, take the whole beach under fire. And behind the advanced defensive positions, the terraced slopes of the hills offered space for more trenches, machine-gun nests and minefields.

The defence of Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach, as part of the Atlantic Wall, was quite well prepared for a possible invasion even though it was only moderately marshalled, especially in the places between the beach roads and between the high and low tide lines, an intricate system of pointed, deadly barriers had been placed, which seemed to make the passage of any vessel larger than a rowing boat impossible. But all these things had been studied in detail by small groups who had visited the beaches at night and from countless aerial photographs.

Omaha Beach had no secrets or surprises. Even the addition of a new, particularly strong division had not hidden from British intelligence and had been passed on to the American 1st Army. Unfortunately, this message was suspicious to the 1st Army command and the storm troopers were not informed. Yet it is hard to imagine that they were not prepared for the worst. For the attack on this magnificent defensive position, General Bradley had refused Hobart’s excellent assault armoured vehicles and only after some hesitation had he accepted DD tanks.

The rough water

At 3 a.m. on June 6, Force 0, which numbered 34,000 men and 3,300 vehicles and would be followed a few hours later by an almost as strong force, began to launch attack boats about 12 miles (19 km) from shore. Four hours of confusion followed, with men struggling blindly against the sea, prey to the utmost despair and misery. As the larger vessels moved closer to the beach, struggling to reach their designated positions, the smaller craft were exposed to the full force of the north-westerly storm, fighting the waves, pounding heavily and making water so fast that the pumps could not keep up.

Some of the big ships had launched their attack boats with their full baggage, but others had let the men clamber overboard into the wildly rolling and pounding boats. The operation was a torture for those men who suffered from seasickness. The sea, which had been hostile during the crossing anyway, became in a few minutes a shapeless, wildly swaying, dark jungle, in which men and boats fought for their lives like the damned in a labyrinthine network of flakes of foam.

Ten vessels sank almost immediately and more than 300 men had to fight for their lives in the darkness. Rudderless boats, half-sunken craft and floating wreckage made it even more dangerous for the men in their life jackets.

In nearly 200 assault boats, the crews and troops, who would soon have to fight the enemy on an open beach, huffed and puffed with their helmets what they could, in some boats seasick to the last man, in all boats wet and cold to the skin. When the men were close to a nervous breakdown and had almost no strength left, the boats finally approached the beach. Then came the next horror: landing.

The first wave

The men in the front boats were more defenceless than they realised, if they had cared at all. The sea had systematically robbed them of their guns and armoured vehicles, and the groups of combat engineers were in equally bad shape. With reckless irresponsibility, the commander of a tank landing craft with 32 DD tanks, which was to reach the beach at H-5, let his heavy vehicles go into the water 6000 metres away from the beach. Even with very experienced crews there would have been little hope for those tanks; now 27 of them disappeared into the waves within minutes. Two others made it to the beach thanks to brilliant seamanship (and a large dose of luck). Three others escaped the fate of the 27 because the landing craft would not lower them and were carried further to the beach. Thus, of the 96 tanks, which should have provided essential close support to the 1450 men of eight companies and the first wave of engineers, barely two-thirds remained at the time of the attack.

The attempts to move the supporting artillery to Omaha Beach in DUKWs were also a resounding failure. The small, overloaded vessels, virtually unmanageable, sank quickly. The 111th Field Artillery Battalion lost all but one of its 105-mm howitzers. The 16th Infantry gun company suffered the same fate and the 7th Field Artillery Regiment was not much better off. The Engineers, who had to transfer the heavy equipment from LCTs to LCMs, also had great difficulties and suffered heavy losses. Nevertheless, a large mass of men, guns and armoured vehicles eventually approached the dangerous surf.

The losses up to that point were far less than those which an enemy with a moderate sea and air force could have inflicted. But the sea and air were dominated by the Allies. With 40 minutes to go before H-hour, the strong firing squadron opened fire on the coastal defences with a large arsenal of weapons ranging from the 40-cm guns of the battleships to the 7.5-cm guns of the destroyers. The heights of the coast were obscured by smoke and fire. At the same time, 329 of the 446 Liberators, which had taken off for the purpose, attacked 13 targets on and near the beach with more than 1,000 tons of bombs. The lead attack boats were still some 800 metres from the beach when the gunfire behind them stopped and the deafening noise subsided.

Exploding mortar bombs and shells and machine-gun bullets hitting the landing craft warned the storm troopers that the enemy was in their sights. The cries of men in the water, the sudden columns of fire, the thunderous explosions when craft were hit by enemy mortar fire or grenades, all shook the men’s insolence and then, at last, the landing crafts went down.

No craft landed on dry sand. The assault boats and the larger LCVP’s and LCM’s ran aground on the sandbanks, sinking crookedly into the beach channels. Dozens of men jumped and tumbled into the water which reached them up to the waist or even to their chests. The sea was lashed not only by the wind, but also by mortar bombs, grenades and machine gun fire. While isolated groups waded towards the beach, half-dazed and confused by the desolation of that nearly ten-kilometre-long wilderness of sand and water, blinded by the smoke of many fires raging on the hills, not knowing exactly what to do, others found themselves in the hell of exploding ammunition and genie loads set off by direct hits. Here and there a landing craft burst into an inferno of smoke and flame. The LCTs of the 743rd Tank Battalion, in the vanguard of the right flank, dashed towards the beach. On the left and right, men from stricken craft dived for cover into the waves, while others tried in vain to hold their ground in the wild water and reach the beach. Some, collapsing under the weight of their equipment, crawled through the water on all fours; others dragged wounded comrades with them.

A direct hit on the forward LCT killed all but one company officer, but eight DD tanks landed on the edge of the beach and opened fire on the Vierville bunker: 200 metres away. The tanks of the 743rd reached the beach further east, but the men without armoured vehicles had little chance. As the guns of the forward attack boats went down, the fire of the enemy machine guns cut through living flesh, so that within seconds the forward spaces of the boats became raw wounds, from which blood gushed. Dozens of men jumped to all sides to try and save their lives.

Within half an hour of H-Hour, there were at least 1000 infantrymen and engineers on the beach and in the sea in front of it, but they were not fighting the enemy; they were simply fighting for their lives and many were too exhausted to drag their equipment onto dry land. Only a few had enough strength left to storm the enemy positions.

Great loss and confusion

Some went back into the water and let themselves be carried away by the tide, which eventually threw them, like wreckage, onto the meagre protection of the seawall or the gravel bank. Only a few of those who had ended up scattered along the entire length of the beach, all of whom had been trained for the special tasks they had to perform, knew exactly where they were. Only a few had reached the beach in those ‘stages’ that they knew from the exercises. Boat crews, who had been taught to fight as units, were hopelessly split up; one detachment was here, the other 200, 300, maybe 1000 yards away. Many of them only knew that they were somewhere on the beach, which had been given the name Omaha Beach. The sea was behind them and the blinding smoke, which in some places protected them from the enemy fire, made them dizzy. The few officers who were there needed some time to orient themselves or decide what to do. Few were capable of leadership in those first hours, when they might have had a chance to get off the beach. Above all, they were exhausted. And there was no protection anywhere.

But despite their crippling losses, and despite being exposed to the full force of the enemy’s defensive fire, the engineers tried to salvage as much equipment as they could and to create openings for the follow-on forces. Heavy mortar and cannon fire detonated series of high explosive charges, which had been fitted with great difficulty and risk of death, so that whole detachments of engineers were airborne before they could get to safety. The rapidly rising tide washed over their legs and the barriers at the far end of the beach disappeared under water. The survivors had to make their way to the sea wall and the gravel bank before they had completed even a tenth of their task. Throughout the 116th Brigade’s sector, they had made two openings. Further east, where hardly anyone had reached the beach, four openings had been cleared, but only one of them had been marked. This work had cost more than 40 per cent of the engineers’ strength, largely in the first half-hour.

The breakthrough at Omaha Beach

But behind the engineer, not only did the tide rise, but the great tide of men and vehicles pushed further and further towards the shore, wave after wave. After three terrible hours, the edge of the beach had become a wilderness of wrecks, of burning vehicles, of destroyed craft and of dead men. Not one exit from Omaha Beach had been forced, not one defensive position had been stormed, and a message went out to the ships off the coast not to send any more vehicles, only soldiers. And yet… long before the destroyers of the maritime force came within 1,000 metres of the coast to fire on the enemy positions, something of order began to grow out of the chaos.

The men, whose lives had been stretched to the limit, got back on their feet, raised their heads again and began to fight… and not just for their lives. They had paid a terrible price for General Bradley’s refusal to use the specialised armoured vehicles Montgomery had offered him, which were the ‘can openers’ for Normandy. Only 100 tonnes of the 2400 tonnes urgently required on D-Day reached the beach. But at last the men, reinforced with the waves of the battalions in second line, pulled off the beaches.

It did not look very hopeful for the generals in the command ships, but the outer hard crust of the defences had been broken and the enemy had no reserves. When darkness fell, the Germans had lost the battle for Omaha Beach, but the Americans did not know they had won it. Meanwhile, on the eastern flank, the British and Canadians were fighting and had already broken through further.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error