Luftwaffe and Navy on D-day

The Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine on D-Day had little influence on the final outcome of the battle. However, it is interesting to consider what influence these forces of the German army could have had during the landings, had the relations with the Allies been different.

The Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine on D-Day

On the one hand, Nazi Germany had seen its air force considerably reduced in number as the war progressed. In the months before the landings, it was also constantly bombarded during Operation Pointblank.

On the other hand, the countless U-boats and battleships of the Kriegsmarine had been consumed by the repeated attacks on the Allied convoys crossing the Arctic, between the US and Britain. In addition, thanks to an increase in production, the American fleet had grown considerably over the years, so that the Kriegsmarine was no longer a worthy opponent for this Allied supremacy.

The Kriegsmarine during D-day

The small fleet of Admiral Theodor Krancke, commander in chief of the German Maritime Group West, was the only real fleet still active between the north coast of France and Great Britain. The fleet consisted of about sixty vessels of all kinds. It was confined to harbours under constant Allied air attack. Combat encounters in the Channel had reduced his destroyer force to two operational ships. Otherwise, he had two torpedo boats, thirty-one motor torpedo boats and a handful of patrol boats and minesweepers at his disposal. In addition, fifteen of the smaller submarines would be made available in Atlantic ports.

The only form of ‘real’ resistance the Kriegsmarine could offer during the landings was rather indirect. The coastline in Normandy was for a large part strewn with sea mines that had proven their success during D-day. Numerous Allied ships were disabled or in trouble by them.

In the days after D-Day, after repeated attacks, some U-boats managed to knock out a number of Allied ships, including: the

HMS Blackwood, the Columbine, the SS Maid of Orleans and a few others.

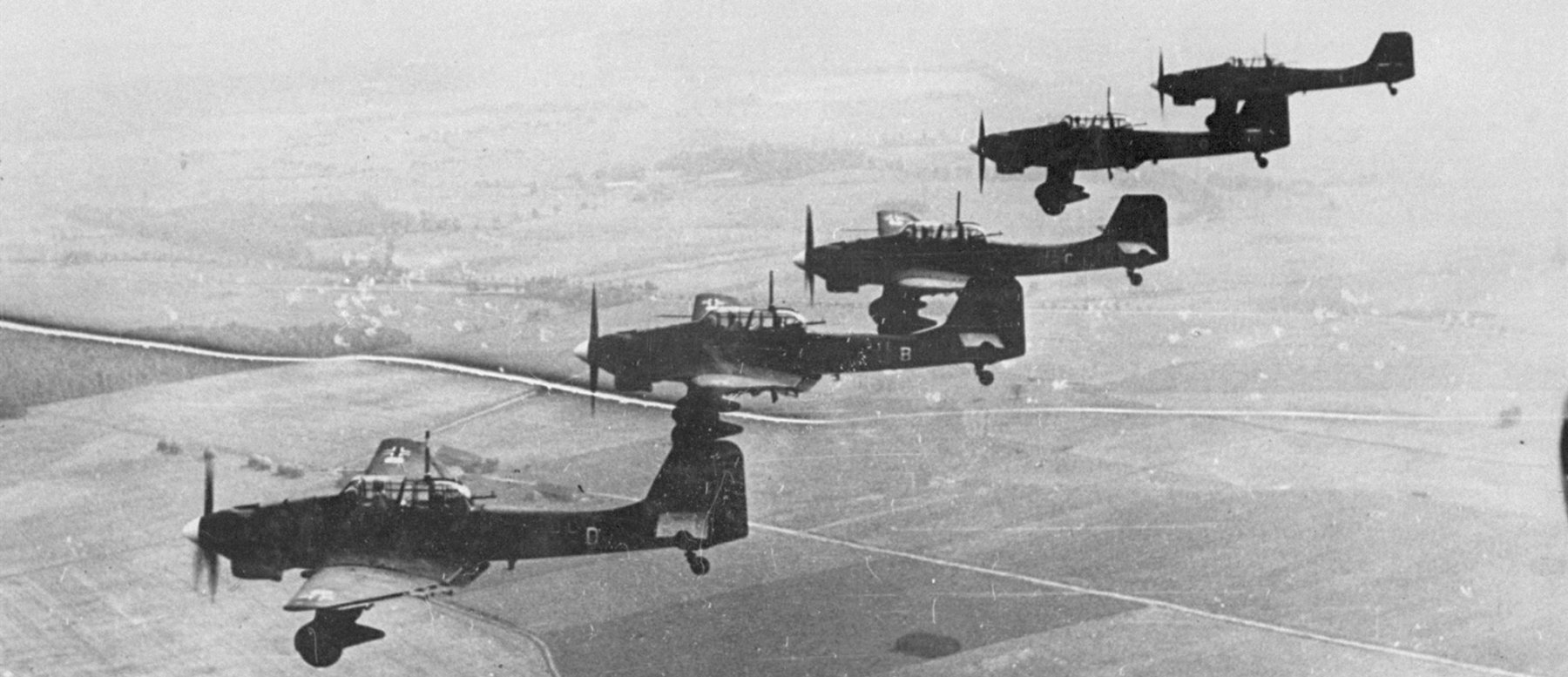

The Luftwaffe during D-Day

The German Luftflotte III, commanded by General Hugo Sperrle, was also hopelessly weakened. It had to manage with half-trained pilots, and its effectiveness, also because of its reduced strength, was therefore poor. The aircraft were exposed to constant attacks by the Allied Air Force, on the ground as well as in the air. At the beginning of June 1944, Luftflotte III had about 400 operational aircraft on paper. Also on paper, these were divided between the 4th and 5th Fighter Aircraft Divisions belonging to the 2nd Fliegerkorps. The primary task of the planes of the 4th Division was to intercept Allied bombers who were going to attack the Reich, but they could be given another task in case of Allied attack landings.

On D-Day, neither the 2nd Fliegerkorps nor its divisions turned out to have any aircraft available for effective action. The promised fighters, supposedly on their way from Germany, mostly failed to show up. Most of the pilots did not know France; only a few of them could read maps properly. The Chief of Staff of the 2nd Fliegerkorps estimated that he had at most fifty aircraft under his command.

So there was no force at sea or in the air that could take on the Allies, and Rommel was under no illusions about his task.

The German armies in the West, constantly harassed from the air, lacking vehicles, poorly trained, and with their radar systems down, could do nothing but sit back and wait for the big battle.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error