American airborne landings

On the evening of June 5, about half an hour before sunset, when the lead ships of the sea attack force entered the defined shipping lanes, bound for France, the Pathfinders of the American and of the British air forces took off from their airfields in England to light their beacons in the fields of Normandy. In this way the American airborne landings could better take place because of the marked drop zones that should have been visible to the pilots. This turned out not to be as simple as it seemed.

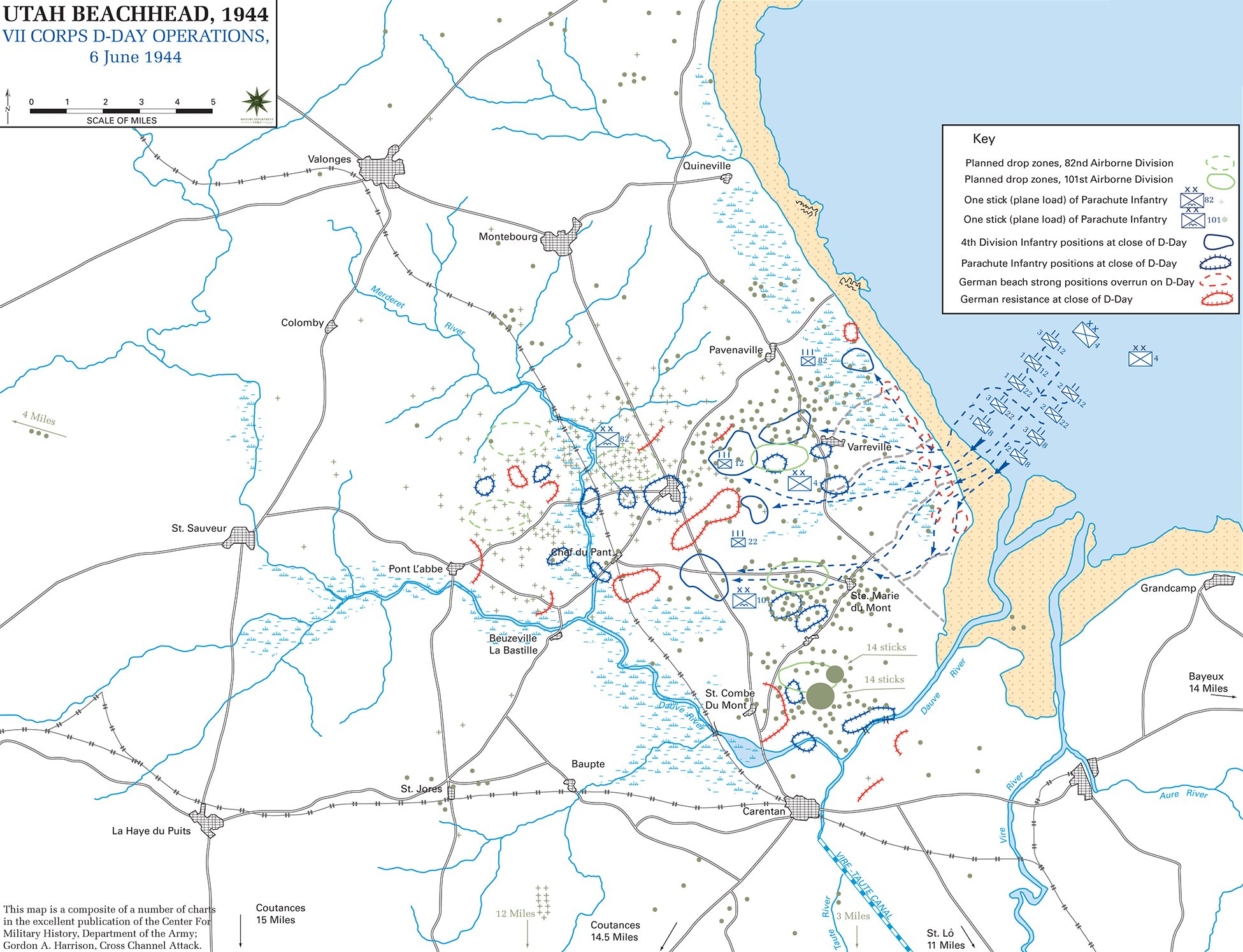

Shortly after midnight, these small vanguards of elite troops were quietly doing their work in enemy territory. The British to mark the jump-off zones of the 6th Airborne Division north-east of Caen, on the eastern flank, the Americans to mark similar jump-off zones on both sides of the Merderet and along the Carentan road and in the vicinity of Sainte-Mère-Église.

Behind them followed 1200 aircraft, bringing nearly 20,000 men to the battlefield. Behind them came the gliders, for whom the paratroopers had to prepare the ground. The Americans threw, during these American airborne landings, two divisions into the battlefield. The 82nd Airborne Division and the 101st Airborne Division.

The landing of the American 101st Airborne division, which had been so carefully prepared with the information available, covered on the map an area 40 km by 25 km wide, while small isolated groups came down even further away. Few of them had even the slightest chance of joining the division. The men were, it seems, given up to the wind without a second thought and ended up in the areas behind Utah Beach.

The American 82nd Airborne Division fared a little better, thanks mainly to one regiment coming down fairly close to the targets, but only 4% of the rest of the division ended up in their zones west of the Merderet. Therefore, the division’s tasks west of the Merderet and at the Merderet and Douve crossings could not be accomplished. The division had become a regiment.

It is getting light…

At daybreak, after the British and American airborne landings and as the amphibious landings from the sea began, the 101st Airborne Division (6600 men) numbered only 1100. By evening, its strength had grown to 2,500 men. The 82nd Airborne Division, which lost at least 4,000 men on the first day, was down to one-third of its strength three days later. Both divisions had lost large quantities of equipment and almost all their glider-borne artillery, most of which had fallen into the Merderet and the Douve.

But the remarkable fact was that this dispersal of men had created such a confusion among the enemy that it was impossible to send reserves to support the defenders of the beaches. By the time the American 4th Infantry Division arrived to land on Utah Beach, the battle in that sector was effectively won.

No coherent story has ever been distilled from the scattered fighting that day by the isolated groups of airborne divisions. It is unlikely that such a story could ever be compiled. The individual achievements of many men, who fought bravely alone, or in groups, will never be known. Yet author Ian Gardner managed to compile many of those individual achievements from the actions of the 101st in the book ‘Tonight We Die As Men’.

The Pathfinders of the airborne divisions did not do a good job. Many failed to find and mark the jump-off zones; some beacons were missing altogether, especially west of the Merderet in an area crawling with Germans; others were misplaced.

In addition to the Pathfinders, there were also battle groups such as the ‘Filthy Thirteen’ whose orders were to attack behind enemy lines and eliminate obstacles or defences before the initial British and American airborne operations began.

First-time pilots, many of whom had been ‘inadequately briefed’, took wild evasive action, lost their way in the clouds and overran their targets. Many approached their targets too quickly and too high, making parachuting especially dangerous.

Major General Maxwell Taylor, commander of the 101st, was dropped with a core of his divisional staff. He strained all day to make contact and bring some order out of the chaos. He felt ‘alone on Cotentin’. In the end, one can get a vague picture from the reports of half a dozen colonels, each trying to gather a group of 75 to 200 men around him, helped by the significant click-clack of the crickets, an instrument for making a click-signal, with which all men were equipped.

By a rare coincidence, a small group of men had the opportunity to kill the commander, Lieutenant General Wilhelm Falley, of the German 91st Division as he returned to his headquarters from a meeting. As a result, the German 91st Division, which had been specially trained in defence against attacks by airborne troops, was deprived of its commander and severely handicapped.

While many German officers believed that this was the beginning of the great Allied attack that had been so long expected and that the battleground was Normandy, others doubted it, including Lieutenant-General Speidel (Rommel’s Chief of Staff) and General Blumentritt (von Rundstedt’s Chief of Staff). As a result, German military machinery was set in motion far too slowly, the small reserves were held back, the tanks remained idle, Rommel out of contact, and Hitler remained asleep. All these circumstances gave the airborne troops on the western flank an advantage of which they were of course initially unaware, but which saved them from the danger of being destroyed.

Sainte-Mère-Église

The story of the 82nd Airborne Division is quickly told. Two regiments of it, whose job it was to clear the area west of the Merderet in the bend of the Douve, were not in the fight. Therefore, one regiment had to save the honour and fight the only clearly recognisable battle. While dozens of men tried to get out of the marshy country along the Merderet to dry land, the third regiment had come down in a rather closed group north-west of Sainte-Mère-Èglise. This was due not to chance but to the determination of the pilots to find their targets.

Long before daybreak, Lieutenant-Colonel Krause, who had landed with about a quarter of his battalion on the outskirts of Sainte-Mère-Église, captured the town without waiting to gather more men. He took the enemy completely by surprise and immediately began to establish a firm base. By noon the town was firmly in his hands.

The 82nd Airborne Division had come down on the edge of the German 91st Division’s assembly area and its position from the start was far more dangerous than that of the 101st Division. All the troops, however fragmented, were immediately surrounded by enemies and scarcely had the men come down or they were fighting for their lives. Some small groups of 50 to 60 men fought all day long in the trenches and hedges, sometimes less than 1,000 yards from other groups with whom they could not make contact. Sometimes they did not even know they were there.

The result of the American airborne landings

The performance of the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions on D-Day can only be judged by fragmentary events. By the end of the day the divisions had failed to make full contact. One as well as the other thought that it had lost at least two-thirds of its troops in the American airlifts. Neither one nor the other had any reason to be satisfied and neither had any inkling of what had happened. They could do nothing but wait for the new day to dawn.

Fortunately, the enemy was in a state of confusion. Endlessly bombarded from the air, hampered by the fact that a conference of senior officers was in progress at Rennes at the very time of the attack, the disunion of the Germans, whose communications were broken and who seemed to have had a premonition that everything would go wrong, was as fragmentary as that of the paratroopers. Many surrendered without a struggle.

Major von der Heydte, commanding the German 6th Parachute Regiment, probably one of the best enemy regiments in the Carentan area, said he had great difficulty in getting orders from his superiors. From the church spire of Sainte-Come-du-Mont he could see with his own eyes the attack from the sea on the western flank. It seemed to him almost peaceful, strangely unreal. The sun shone in the afternoon and the whole scene reminded him of ‘a summer’s day on the Wannsee’. The great bustle of the landing craft, with the vague grey shapes of the warships in the background.

Von der Heydte sent his three battalions into battle, one to the north to attack Sainte-Mère-Église, the second to the north-east to protect the seaward flank at Sainte-Marie-du-Mont, the third to Carentan. Von der Heydte lost contact almost immediately. The organised resistance on the western flank had crumbled.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error