Artificial Mulberry harbours

The Mulberry artificial harbours were ingenious structures of immense size and complexity. These floating harbours provided port facilities to the Allies during the invasion of Normandy until the port of Cherbourg was captured.

To win a war, you need equipment. The battle in Normandy was a war of attrition so the provision of the necessary equipment was a factor that would determine the success of the Allied advance. There is still uncertainty as to who exactly devised the artificial Mulberry harbours but we do know that Hugh Iorys Hughes, a Welsh civil engineer, Professor John Desmond Bernal, and Vice-Admiral John Hughes-Hallett, among others, each contributed to the final plan.

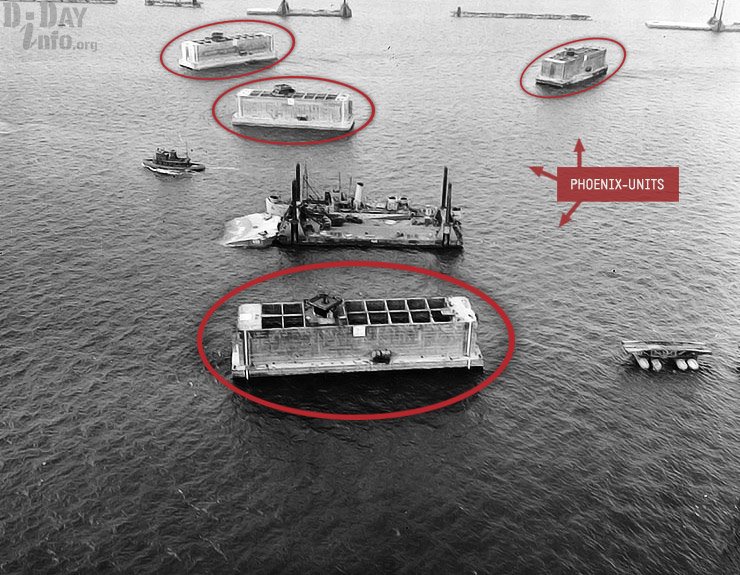

Protected by breakwaters called Gooseberries, the Mulberries were fairly intricate and consisted of steel and concrete caissons (Phoenix units), so-called ‘Beetles’, and old ships that had fallen out of service. A total of 146 Phoenix caissons were required, ranging from ten small ones, each weighing 1672 tonnes, through six intermediate sizes, to 60 large ones, each weighing 6044 tonnes. In their manufacture, 600,000 tonnes of concrete, 31,000 tonnes of steel and 1,350,000 metres of rebar were used. The eight dry docks and the two wet docks that had been cleared with great difficulty were to be supplemented by twelve large holes dug below the water level in the banks of the Thames, the excavated earth forming a rampart between the hole and the river. When the caissons were completed, the earthen wall was dug through so that the caissons could be towed up the river. 20,000 men worked under high tension for months, while the pumps fought relentlessly against the incoming water.

But it was not enough to make those strange objects that presented the enemy’s air reconnaissance with an unsolvable riddle. Not only did they have to float, they also had to be able to sink quickly in water of a depth commensurate with their size. After much experimentation, the sinking time for the largest caissons was reduced from one and a half hours to 22 minutes. Each Phoenix was also a ‘sort of ship’, with quarters for the crew and equipped with two Bofors anti-aircraft guns with 20 tonnes of ammunition. However, they could not move under their own power, and when they were ready, the towing mechanism proved not to be strong enough. Crews from the Chatham naval shipyard worked day and night during those final weeks to make the big barges safe for the tugs.

The safe passage of 146 of these ‘monsters’ was just one of the many towing problems to be solved with a large fleet of tugs. The tugs would have to bring the pieces safely from the artificial Mulberry harbours to the other side of the English Channel and manoeuvre them exactly in their predetermined positions, where the slope of the seabed determined the size of the caissons. Furthermore, the 70 old ships were towed to the other side and sunk there to form the Gooseberries.

The ‘artificial harbour project’ involved a total of more than 3,000 vessels, manned by 15,000 personnel. There was not much time for practice; the dress rehearsal was also the premiere. The heads of the piers, each consisting of 1000 tons of steel, had to be fixed to the beaches, and the huge mass of material hanging behind them, the thousands of metres of ‘floating bridge’, had to be able to move up and down almost seven metres with the tide. In this way, Admiral Ramsay, commander of the Allied maritime forces, hoped to build a solid bridge to France and to be able to deliver 12,000 tons of supplies a day to 33 divisions that had to have food and ammunition. For this enormous quantity would be demanded at the height of the supply situation via the Mulberries.

The Mulberry artificial harbours consisted of two parts:

- Mulberry A was the harbour established on Omaha Beach (sectors Dog Red and Easy Green) at the village of St-Laurent-Sur-Mer. This Mulberry was a lot smaller than Mulberry B and consisted mainly of 3 small piers one Goosberry breakwater and Phoenix caissons. The harbour was only partially attached to the mainland. The harbour was therefore largely destroyed during the storm of June 23. The usable parts of Mulberry A were later transported to Mulberry B in Arromanches, which was less damaged, to replace parts of the harbour here and there.

- Mulberry B was the most important and largest artificial port of the two. It was constructed on Gold Beach, at Arromanches. It consisted of 3 large and 1 small pier surrounded by numerous Phoenix caissons and one Goosberry breakwater. The Mulberry B was taken out of service after 6 months when the Allies had access to the big port of Antwerp.

Pluto

Besides the Mulberry artificial harbours, another project was designed: Pluto (Pipeline-under-the-ocean = pipeline under the sea). With this pipeline, oil would be transported from southern England to Cherbourg, and later to the French and Belgian coasts, which were easier to reach. It is perhaps too weak to call all these activities complicated by the work that was attached to the more than one hundred kilometres long Atlantic Wall; yet it is not so far from the truth. Admiral Sir William Tennant, who as a captain-at-sea had done great deeds on the beaches of Dunkirk, with a naval staff of 500 officers and 10,000 men, made sure that the Mulberry project came together, apart of course from the large army of workers involved.

The whole project was part of an admirable set of organisations that bore all kinds of ‘secretive’ code names. These names led, from then on, a brief life in the language of the various departments, giving them their own jargon. Buco’ meant ‘build-up control’, the organisation that monitored the progress of the build-up. There was a ‘turn-round control’ (prosecuting the return voyages from the coast of France to England) called ‘Turco’, ‘Corep’ for the organisation in charge of controlling repairs, ‘Cotug’ for the control of the tug organisation, and from these smaller departments emerged with their own arcane names.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error