Operation Pointblank

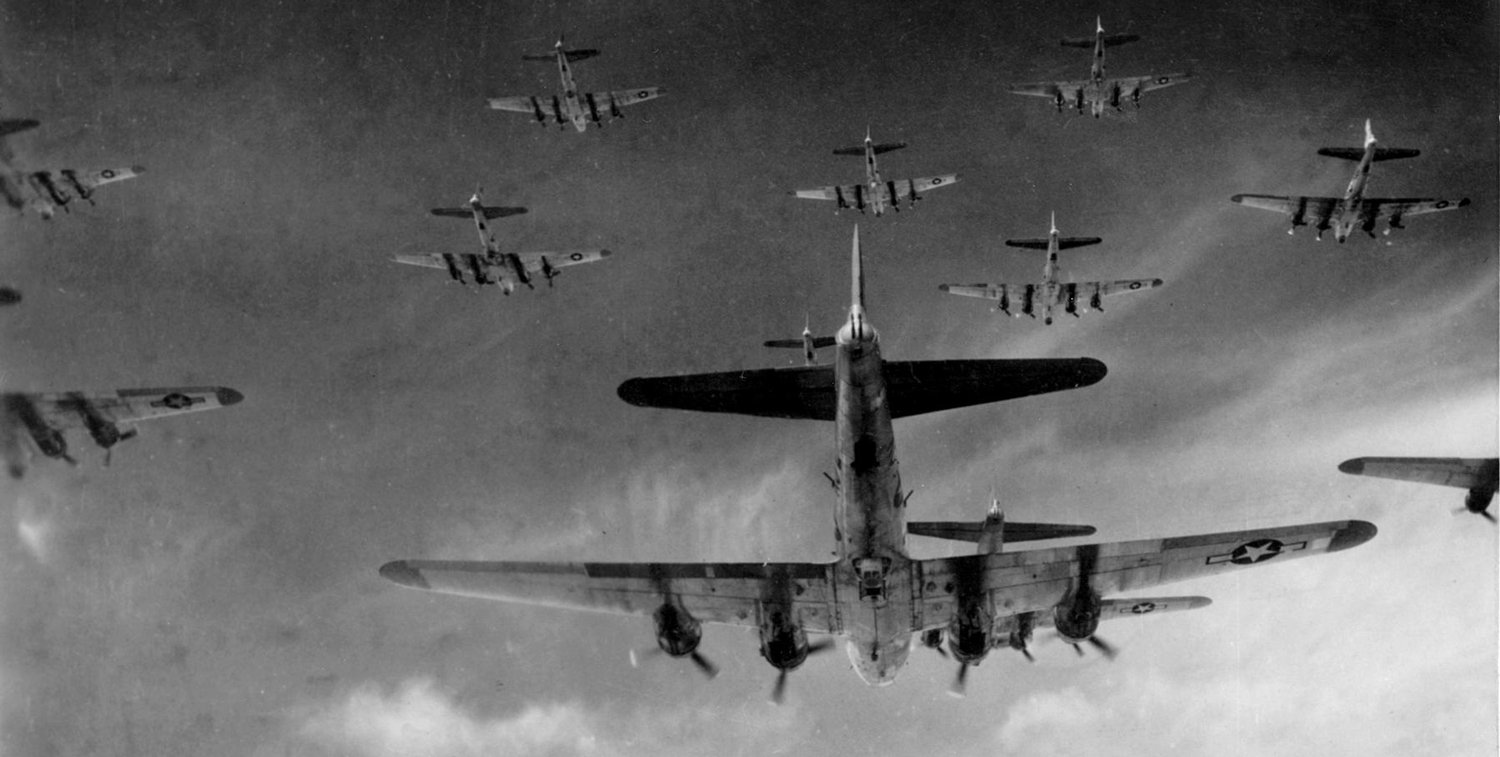

The primary objective of Operation Pointblank was to weaken or destroy the German presence in the airspace. This was to prevent the Germans from providing air support to the front lines and to ensure that the Luftwaffe would not play a significant role in the invasion of Western Europe (D-day).

In July 1943, COSSAC expressed its concern:

“The main characteristic of the German air force in Western Europe is the unceasing growth of the fighter strength which, if not checked, could reach such a size that an amphibious landing is unthinkable. It is therefore necessary, in the first place, that German air strength be reduced and diminished between now and the time of the attack … That condition, more than any other, will determine whether an amphibious assault can be launched at a given date.”

About a month earlier, it had become clear at a higher level that unless the enemy’s air strength was broken, ‘it would be literally impossible to carry out the planned bombing raids’. A new plan was drawn up, called Operation Pointblank, which gave priority to the destruction of the German Luftwaffe without losing sight of the goal of the bombing offensive.

The importance of the air force, especially for the success of Operation Overlord, was fully realised in the summer of 1943. The combined bombing offensive was agreed at the Casablanca conference in January. This offensive was intended to destroy the enemy’s economic strength and undermine the morale of the German people, but for the time being the offensive had not yet produced results with which to be satisfied. The order for Operation Pointblank was confirmed at the Quebec Conference in 1943.

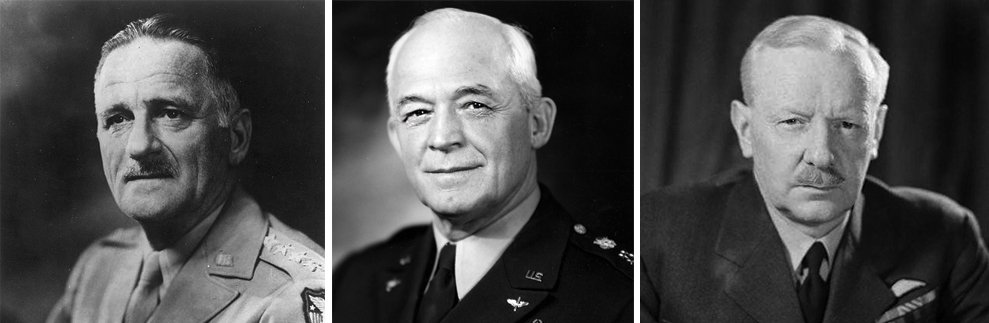

Allied air power, especially the bomber, had brought a new dimension to warfare. Despite results that were inconclusive, to say the least, and the continued growth of the enemy fighter force, the commanders of the Allied Strategic Air Force had come to the conclusion that they had the decisive tool in their hands: that they could achieve victory all on their own. General Spaatz, commander of the United States Strategic Air Force (USSTAF), even believed that Overlord was unnecessary.

Air Chief Marshal Harris of RAF Bomber Command, his British counterpart, agreed with him. General Arnold, the US Air Force representative to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, had come to a similar conclusion. None of these commanders objected to Overlord; none of them were annoyed by the demands made on their forces. They believed that if they continued with their bombing offensive, things would sort themselves out and the objectives set would be achieved.

Command during Operation Pointblank

The attitude of the ‘barons of Bomber Command’ made it inevitable that a serious command crisis would follow the appointment of a supreme commander for Operation Overlord. General Eisenhower soon pointed out. ‘The strategic air weapon is virtually the only weapon available to the commander-in-chief to influence the general course of the battle’.

No commander-in-chief could have swallowed the attitude of the air force commanders because it infringed on his command authority. If he was not in command of the air force, the commander-in-chief was powerless, could only give the signal for the attack and would then have to wait for days, perhaps even weeks, without being able to effectively influence the course of the battle. Eisenhower’s statement to Churchill on March 3 that he had nothing left ‘but to go home’, and his subsequent message to Washington, dated March 22, that ‘unless the matter was immediately settled, he would ask to be relieved of his command’, was in no way an exaggeration.

The point was that the Commander-in-Chief, in his conflict with the commanders of the strategic air forces, and to some extent with the British Prime Minister and the Chiefs of Staff, emphasised the fact that land, sea and air forces had become three branches of a single weapon. A commander-in-chief had to command all three branches, and in doing so it was inevitable that they would have to give up some of their identity.

Incidentally, the demands of Overlord and of Pointblank were not incompatible. Eisenhower had made it clear that he also wanted command of the air force, but that he was not at all thinking of interfering with Coastal command, for example. He did not agree with the strategic objectives pursued by the bomber commanders to a certain extent, but he and his staff had to have the right to make clear and assert their views on the use of air power in direct connection with Overlord. They had to have control of the air force, at least at the landing stage and especially now, in the last ninety days before.

Result of Operation Pointblank

The prolonged attacks on the German aircraft industry had reduced production by 60 per cent. According to records, 5,000 enemy aircraft had been destroyed between early November and D-Day. These facts, together with the continuous attacks on enemy aircraft and the enemy losses of trained pilots, meant that there was no longer any need to fear the actions of the German Luftwaffe during D-Day and the Battle of Normandy.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error