GARBO: double agent in the interest of D-day and Operation Overlord

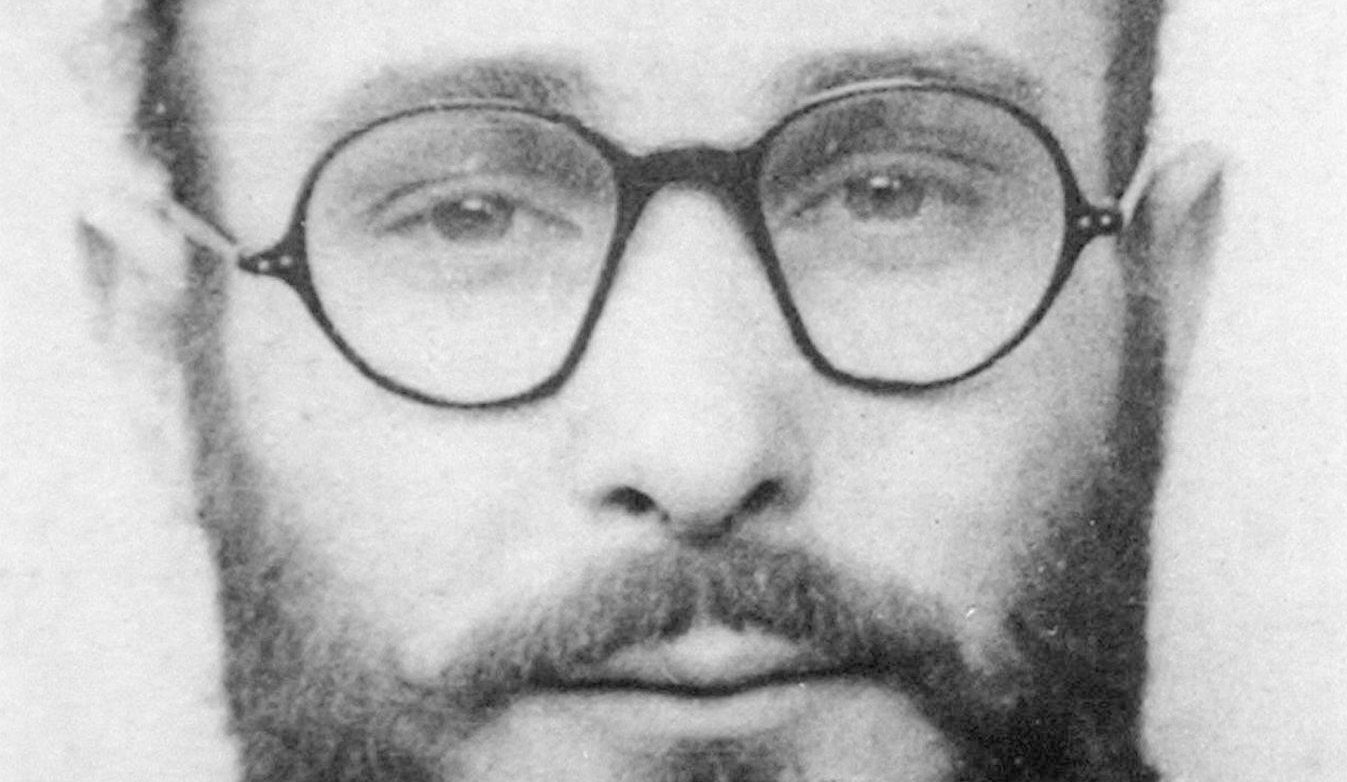

GARBO, then better known as Pujol, was born in Barcelona on February 14, 1914. The third of four children, he was sent to Valldemia boarding school run by the Marist Brothers in Mataró (32 km from Barcelona). He stayed there for four years. The students were only allowed to leave the school on Sundays when they had visitors. Only his father came to visit him every week.

In the 1930s, he was called up to serve in the Spanish Nationalist Army under Franco’s leadership. Because he himself had very different ideas about Franco’s politics and the future of Spain, he began to wonder how he could make himself useful in helping to overthrow Franco’s dictatorial regime.

Independent spy

In 1940, at the start of the Second World War, Pujol decided that he had to make a contribution in the interests of humanity (and thus oppose the Franco regime) by offering his help to the United Kingdom. Which at the time was the only major opponent Nazi Germany had. He initially approached the British no less than three times. However, they showed no interest in hiring him as a spy. Therefore, Pujol decided to join the Germans so that he could offer himself to the British as a double agent.

Pujol created an identity as a fanatical pro-Nazi government official so that he could travel to London on official business. He also managed to get hold of a fake Spanish diplomatic passport by simply tricking a printer into believing he was working for the Spanish Embassy in Lisbon. He was ordered by the Germans to set up a network of agents in the United Kingdom.

Instead, he went to Lisbon. Using a tourist book about the UK, magazines and advertising, he created credible reports that appeared to come from London. He showed that he was supposedly travelling all over the United Kingdom by forwarding his travel expenses, based on prices in a British Railways guidebook, to his German contacts.

After a while, he had already made up an extensive network of fictitious spies in different parts of the United Kingdom. Pujol’s reports seemed so credible that they were even picked up by MI5 (British Counterintelligence Service). In February 1942, after the United States had joined the fray, Pujol approached Lieutenant Patrick Demorest (US Navy), who was fairly quick to recognise the potential of Pujol’s espionage talents. Demorest contacted his British counterparts and suggested that Pujol work with them. Pujol’s plan to work for the British was thus successful.

Pujol at MI5

The British were aware that someone was leading the Germans astray and saw the value of this when the Kriegsmarine wasted supplies after trying to intercept a non-existent convoy. That convoy was in fact made up by Pujol.

Pujol moved, on April 24, 1942, (now for real) to the United Kingdom. He was given the code name BOVRIL, named after the beef extract. When he passed the security checkpoint, which was conducted by MI6 officer Desmond Bristow, he suggested that he be accompanied by MI5 officer Tomás Harris (someone who spoke fluent Spanish) so that he could work with Pujol. Not much later, Pujol’s codename was changed to GARBO, named after Greta Garbo. His wife and children also moved to the UK not much later.

Together, Harris and Pujol wrote 315 letters, averaging 2000 words, to a post office box in Lisbon that were read by the Germans. His fictitious network of spies was so efficient that the Germans did not even find it necessary to recruit additional spies in the United Kingdom.

GARBO was unique among all other British double agents. He was the only one who chose to become a double agent. The others were mostly enemy spies who had been discovered and had to be placed under surveillance.

However, the information that was passed on to the Germans was not always fictitious. In order to maintain credibility, real information was occasionally sent as well, but usually at a point when it no longer had any value.

GARBO and his role in Operation Bodyguard

In January 1944, the Germans told Pujol that they expected a large-scale invasion of Western Europe. Therefore, they asked him to keep them informed in case he could get any information about it. An invasion was coming anyway. It was called Operation Overlord. Pujol played a very important role in Operation Bodyguard, the diversionary plan that had to lead the Germans astray. He sent more than 500 radio messages between January 1944 and D-day (June 6, 1944). Sometimes more than 20 messages a day. During the planning of Operation Overlord, the Allies considered it vital that the Germans be misled into believing that the landings would take place in the Straits of Dover instead of Normandy.

To maintain GARBO’s credibility after the landings, it was decided that the Germans should be told the actual details of the invasion by him but at a time when the Germans themselves could no longer take action. In the night of June 5 to 6, at 3 a.m., GARBO was supposed to be in contact with German intelligence but the German operators, at the other end of the line, did not hear anything until 8 a.m. This enabled GARBO to even inform the Germans about the invasion. Because of this, GARBO could even blame the Germans for being negligent and therefore missing important information. Thanks to this incident, GARBO’s credibility was stronger than ever.

On June 9 (three days after D-day), GARBO sent a message to the German intelligence with which he could even reach Hitler and the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht. GARBO stated that he and his top agents had been able to make an overview showing 75 divisions stationed in the United Kingdom. In reality, only 50 divisions were present. It was in fact part of Operation Fortitude, which in turn was part of Operation Bodyguard, to make the Germans believe that a so-called First US Army Group, of 11 divisions, commanded by George Patton was stationed in the south of England.

This diversion was supported by dummy planes, tanks and trucks. GARBO had to convince the Germans that the First Army Group had not yet taken part in the Normandy landings of June 6, so the landings had to be considered as just a diversion.

These reports by Pujol were considered credible by the Germans. No less than 62 reports of Pujol were included in the German OKW during Operation Fortitude.

As a result, in July and August the OKW kept 2 armoured and 19 infantry divisions stationed near Pas de Calais awaiting the so-called ‘real invasion’. It was Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt who refused to release these divisions (mainly the armoured divisions) to Erwin Rommel, who wanted to send them to Normandy as soon as possible because he was convinced that the landings in Normandy had to be repulsed as soon as possible. This Panzer matter later proved to have a major impact on the final outcome of D-Day and the Battle of Normandy.

Distinctions

Pujol was awarded the Iron Cross (2nd class) on July 29, 1944 for his services to Nazi Germany during the war. This reward was usually meant for soldiers who fought at the front and had to be personally approved by Hitler. This reward was announced to Pujol by radio, the medal itself he received after the war.

From the British he received an Order of the British Empire from King George VI on November 25, 1944.

The Germans never realised that Pujol was a double agent in the service of the British. Pujol was one of the few, or perhaps the only one, to receive an award from both factions.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error