Atlantic Wall

The German supreme command struggled with a shortage of men as most of them were on the Eastern Front. They tried to remedy this shortage by building the Atlantic Wall. The Atlantic Wall ran from northern Norway to France’s border with Spain. The plans to build a large number of fortified positions, bunkers, artillery pieces, anti-aircraft guns, roadblocks and barriers along the coast were already completed in late 1941. At that time, Norway already had a coastal defence line. This had already been set up immediately after the German invasion.

The Atlantic Wall is an enormous defensive work which started to be built in 1942. A construction project of the construction company Organisation Todt. In 1944, the wall was still not finished, despite the efforts of Marshal Rommel (responsible for the zone from the Netherlands to the Loire). The intention was that the coastline of the North Sea, the Channel and the Atlantic Ocean would be defended by 15,000 bunkers. A job that involved 450,000 workers, 11 million tonnes of concrete and 1 million tonnes of steel to arm the concrete. Contrary to German propaganda, the ‘Wall’ was not an unbroken ambush.

Even today, numerous remnants of the Atlantic Wall are visible along the Normandy coast. Behind the wall were troop concentrations of more than 700,000 men.

In February 1944 Rommel issued a directive to his army commanders, and by the end of April he repeated it:

In the short time left before the great offensive begins, we must succeed in making all the defences of such quality that they will be able to withstand the strongest attacks. Never before in history have there been such extensive defences to stop attacks from the sea. The enemy must be destroyed before he penetrates our territory. We must stop him in the water, not only delay him, but destroy all his equipment while it is still afloat.

Again and again he reminded his commanders and his staff that the first twenty-four hours would be decisive.

The obstacles of the Atlantic Wall

Rommel devised an elaborate system of obstacles between the high and low tide lines on the beaches, which would make an approach extremely risky even for flat-bottomed vessels.

-

Widerstandsnest

Widerstandsnest

In the important and strategic places, the Germans often built several networks of bunkers and other shooting positions to defend themselves. The Germans called these positions 'Widerstands nests'. Such a position often consisted of several bunkers connected by trenches. In addition, these Widerstands nests were also shielded from all sides with mines and barbed wire.

The Widerstands nests that lay directly on the coast were also often coordinated with each other. For example, all the nests on roughly the same line could open fire crosswise. This way of shooting was much more efficient as the enemy was more likely to be hit.

-

Tellermine

Tellermine

The counters were plate-shaped, contained just over 5.5 kg of TNT and was activated from approximately 200 lbs (90 kg) of pressure. The Counter Period was capable of destroying a tank or a light-armoured vehicle. Due to the relatively high activation pressure, only one vehicle or heavy object would set off the mine.

-

Barbed wire

Barbed wire

The barbed wires were often installed parallel to the elevations and dunes of the beach. This served as the only visible barrier against the enemy hand. The entanglements of the wire usually began to thin out halfway through the dunes. Also for the embankments the Germans sometimes placed extra wire with small meshes, apparently to slow down the use of the Bangalore torpedoes.

The distance of the barbed wires around defences, such as bunkers, trenches or foxholes, varied depending on the terrain and the importance of the network itself. In most places this distance was about 30 to 50 metres. In other cases this could vary from 60 to 120 metres, or even up to 200 metres in some cases. In general, the distance from the barbed wire to the nearest bunker or other shooting position was not less than 25 metres.

The Germans often use barbed wire to shield all sides of a minefield. These fencing usually consisted of a single row of posts with five or six strings of wire.

-

Anti-tank wall

Anti-tank wall

The Germans built concrete walls at many important defence networks to keep tanks and other vehicles out. Especially in all coastal areas where a strong defence was planned. Walls of this type were often used to block streets and roads behind the dikes, when approaching strategic points and also on the outskirts of important cities. In a coastal town, the Germans often made a continuous wall, parallel to the coast, by joining it in line with the facades of existing buildings.

Before a wall was built, the site first had to be approved on the basis of a formwork. Sometimes a light steel reinforcement was incorporated in the wall, but most of the time the wall consisted mainly of concrete. Often metal hooks were attached on top of the walls to place barbed wire on top. In order to increase the efficiency of the wall, the Germans often dug a ditch in front of the wall. Sometimes just traps, covered with planks and sand.

In areas where there were large quarries, they usually built the wall with the indigenous stone instead of concrete.

In May 1944 the Germans also started building the Ritthem anti-tank wall. The concrete of this wall was extra armed and the entire top of the wall healed towards the enemy making climbing it even more difficult. Also in this wall often foxholes (Tobruks) with machine guns were used.

-

Tetrahydra

The Tetrahydras were pyramid-shaped obstacles made of iron beams covered with concrete. Like the Czech hedgehogs, they were static defensive obstacles against tanks.

-

Czech hedgehog

Czech hedgehog

The Czech hedgehog was a static defensive obstacle against tanks and other heavy vehicles, made of angled iron (i.e., with an L or H longitudinal section). The hedgehog was very effective in preventing tanks from breaking a line of defence. It retained its function even when it was overturned by a nearby explosion.

On D-day, these obstacles offered many Allied soldiers their only protection against the Germans. In the first waves of attack, special units were often deployed to destroy these hedgehogs so that the DD tanks had a free runway.

-

Hemmbalk

Hemmbalk

This diagonal treeramp was installed (below the tide line) to disable or destroy landing craft. The tree trunk was mounted up, away from the sea, and supported by two or three other beams. Each disaster was armed with steel teeth (Stahlmesser) or Countermines or both.

-

Hochpfahlen

Hochpfahlen

The Hochpfahlen (or laminated poles) were the most common obstacles on the beaches of Normandy. They consisted of wooden or metal poles tipped with Teller mines. These were dug into the beach below the tide line to destroy incoming landing craft and vehicles.

-

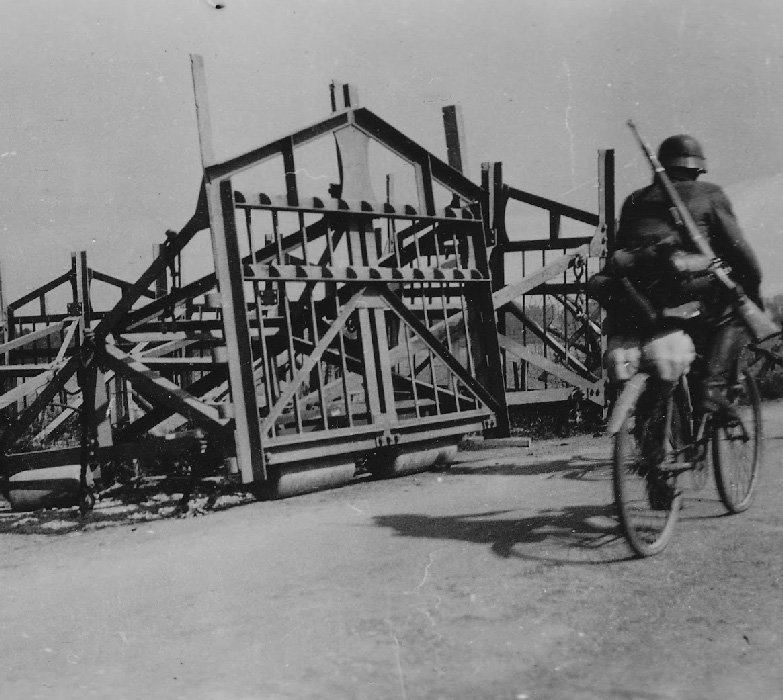

Belgian Gate

Belgian Gate

The Belgian Gate was also known as a Cointet element or C-element. It was a heavy steel gate about 3 metres wide and 2 metres high, mounted on rollers.

The Belgian Gate was the main element in the Belgian KW depot, a tank barrier built between September 1939 and May 1940. A total of 77,000 Cointet elements were produced by order of the Belgian Ministry of Defence, a large number of which were placed on the KW-carrier between Koningshooikt and Wavre. After the German invasion, the Cointet elements were used by the Germans in Europe as barricades on roads, bridges and on the North Sea beaches. Among the Germans, the Cointet element was known as the C-element.

A large number of these Belgian gates were transported to Normandy for the construction of the Atlantic wall. Initially these gates were made to be placed next to each other, but the Germans usually used them on the low-water line alternating with other obstacles such as the Hemming beams. Sometimes they were also placed along the bunkers on the dikes to form a kind of barrier.

He planned to lay 50 million mines as a first line of defence and literally recreate the beaches into great minefields. But there were not that many mines available, and when small quantities finally began to arrive, the minelayers could no longer leave the ports because of the danger of Allied air raids. In the end, at most six million mines were laid, only a little more than a tenth of what he had deemed necessary. Innumerable ‘hedgehogs’ and tank obstacles were erected between the great corner-iron constructions, the ‘tetrahydras’ and the ‘Belgian gates’, which, with thousands of mullioned posts, pointed towards the sea and closed off the approaches to the beaches.

In the area behind the Cotentin peninsula Rommel had planned to construct on the fields and meadows an extensive network of poles (Rommel’s asparagus), interlinked with barbed wire and marbled, as a ground defence against airborne landings.

The shortfall

When the work of the Atlantic Wall in Normandy was supposed to be finished by mid-May, he went to inspect the site and found that the work had barely begun. The 13,000 shells necessary to cause explosions were impossible to obtain. The acute shortage of manpower, materials and mines, and the fact that transport could only be carried out by bicycle, horse or cart, made the implementation of a comprehensive defence plan impossible. Of the ten million mines needed for the 352nd Division’s 50 km front, only ten thousand were delivered. The situation with the 716th and 711th Divisions, defending the front behind the Normandy beaches, was not much better.

By the end of May, only two-thirds of the coastal batteries covering the Army Group front were in casemate positions. A system of fortifications, constructed at an average interval of 800 to 1300 metres, were mostly unprotected. Only 15% of the installations in the sector of the 352nd Division were protected; the rest were barely protected from air attack. According to the 716th Division, the situation was even worse there. The daily requirement of the 7th Army in Normandy to continue the construction of the defences was at least 240 lorries of cement. Records show that in a given three-day period only 47 trucks of cement were delivered. The forced closure of the cement factory in Cherbourg (reason: lack of coal) made the shortage even worse. This closure was actually a consequence of the Allied air raids on roads and railways.

The shortage of labour was so severe that the 352nd Division, which had to defend the important beach area between Grandcamp and Arromanches, had to cut posts itself in the Cérisy forest, twenty kilometres further inland.

These desperate shortfalls caused Rommel to level bitter reproaches at the Luftwaffe. He noted that the Luftwaffe used 50,000 men for maintaining communications, and another 300,000 for ground services. That Hugo Sperrle, commander of Luftflotte III, largely agreed with him, was of little avail. The Luftwaffe was Göring’s private domain. Rommel’s repeated attempts to secure the services of the 3rd Anti-Aircraft Corps in Normandy were thwarted. Göring would not allow his troops to be used in the construction of defences.

As June dawned, there were still disturbing breaches in the defences. Every new invention had been noticed by the Allies and often ‘examined’ by the brave men who visited the beaches at night in complete silence. Because the Zweite Stellung (a second line of defence deeper inland) had been abandoned, the defences lacked depth and formed only an outer crust too weak to withstand the violence of attack. Yet this was not Rommel’s fault. He had tried the impossible, and he had achieved a great deal. He had started with a ‘myth’ and he had given it ‘teeth’. Moreover, he had improved the positions of his troops enormously.

The divisions behind the Atlantic Wall

On the eve of D-Day, von Rundstedt’s command in the west counted 60 divisions of which one, the 19th Armoured Division, was re-equipped after it had taken a beating on the Eastern Front. Since one of the divisions was in the Channel Islands, the effective strength was 58 divisions. Of these, 31 had a static role; the remaining 27, including ten armoured divisions, were as mobile as the Führer’s suspicion and the available resources permitted. They were deployed from Holland to the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts; five divisions in Holland in the 88th Army Corps, 19 on the Strait of Dover between the Scheldt and the Seine, 18 between the Seine and the Loire. 43 divisions of the overall total of 60 had been brought together into General Rommel’s Army Group B, the 88th Army Corps in Holland, the strong 15th Army on the Strait of Dover and the 7th Army in Normandy. Rommel had succeeded in improving and strengthening the positions of the 7th Army under the command of Dollmann. According to him, that army should deliver the decisive battle on the beaches.

Have you noticed a language or writing error? Please let us know, as this will only improve our reporting. We will correct them as soon as possible. Your personal data will be treated confidentially.

Report error